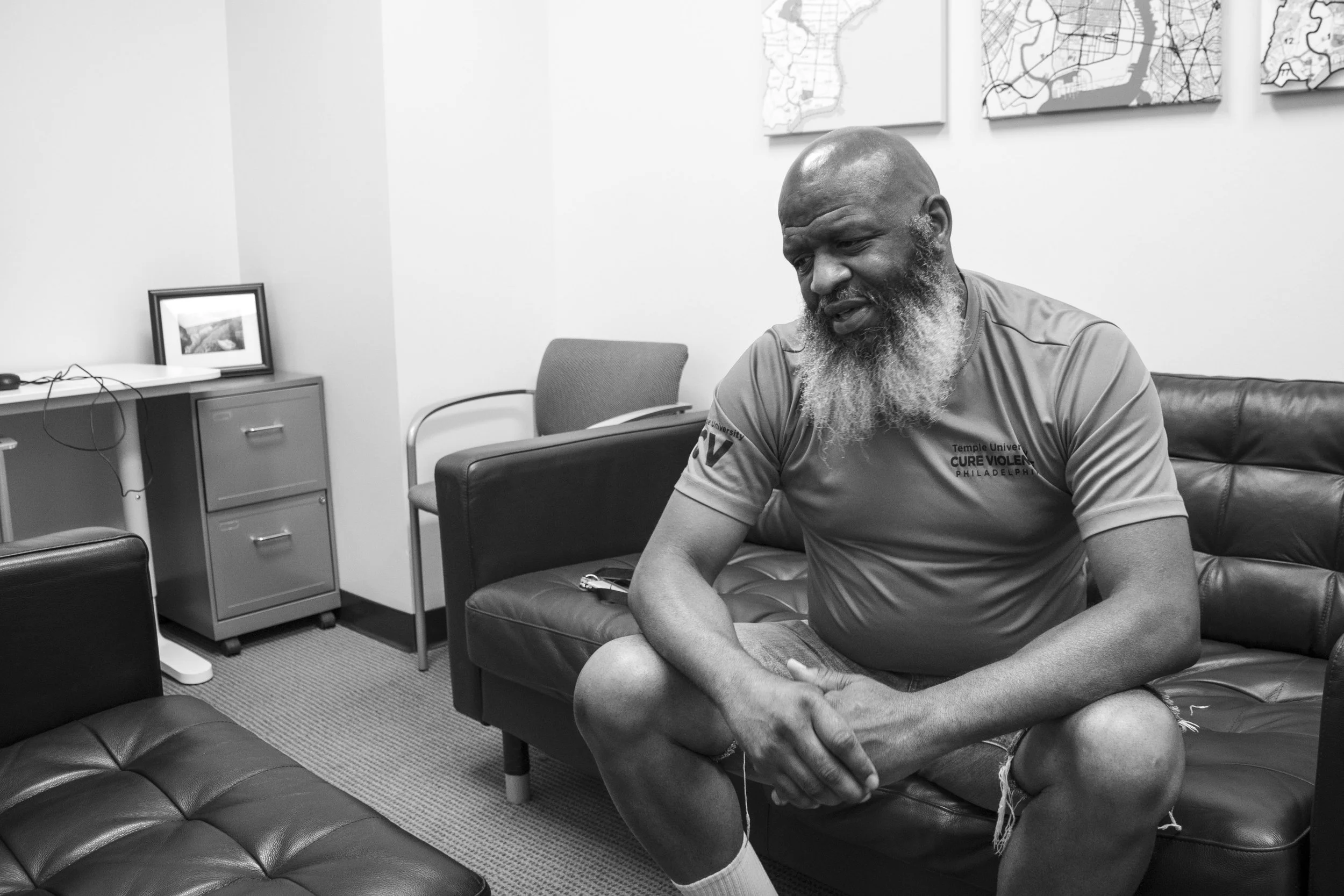

Andre Porter

North & Southwest Philadelphia

Andre Porter’s approachable demeanor and ties to both North and Southwest Philly make him a valuable community leader, though he says he was too shy to take up that mantle initially.

Born in North Philly and raised in Southwest, Porter came up under the reign of the Junior Black Mafia, an organized crime group that dominated the crack cocaine trade in Philly starting in the mid-80s, coinciding with the highest homicide rates in the city’s history. A series of arrests effectively ended the JBM era in the early 90s, but Porter sees similarities between that era and North Philly’s current cycle of violence driven by drug dealing and competition for street cred.

Porter, who was incarcerated himself for hustling in 1999, says the biggest challenge in reducing violence today is a dominant street culture that pressures people to maintain a certain “image,” including clothes, shoes, cars, drugs, and violence. He believes the first steps toward changing that culture are modeling financial stability for young people and increasing accountability among community members.

For the last two years, Porter has worked for Cure Violence Philadelphia, first as a driver and now a street outreach worker. He manages a caseload of 15 participants at a given time, but his reach clearly goes much further – he mentors his son’s friends, considers former participants a family, and leads those around him by example.

North / Southwest

“Me being both sides, North Philly’s different. I always say North Philly is a different animal, streetwise. Their blocks is packed, people outside all the time … They’ve always been outside people. It’s always been outside all day, all night … Southwest, not so much. The competition level is not the same. In Southwest Philly, it might be three on the block. North Philly is 10, all trying to hustle … because it's a big drug market. More people, which I think creates more competition, which creates conflict.

“Southwest, at one time, we had it very bad … We had an era called the JBM era, where it was flooded with hustling everywhere … In that era, Philly had the most murders … It was all really drug related. That’s what's crazy. When someone was shooting, it was really about territory.

“The Junior Black Mafia stretched to North Philly, Germantown, South Philly, they had people everywhere. But in Southwest, that was the era that got us. Because they’d pull up, they’d come in your neighborhood, and they had a slogan: Get down or lay down. Get down with us, or you’re gonna be laying down.

“But once everybody got locked up in the mid-90s, the good thing is that nobody tried to take that spot. Nobody said they’re going with a new crew … With North Philly, it’s once a head is gone, somebody wants to be the next head, so it keeps going. When [JBM] fell, we kinda lost that in Southwest. It was like we changed … But in some parts of the city, if you’re the guy and you fall, somebody wanna get the next spot, and that keeps it the same structure.

“Now Southwest, it’s more low key, more sneaky, because you don’t really see people that much. Certain times of day you’re like ‘it’s empty outside.’ In the JBM era, you wanted everybody to know you was it. You wanted that stature … Now, nobody is saying ‘I’m the next guy.’ But in North Philly, they still want to be known on the block: ‘I’m in charge, it’s my block now.’”

Image

“A lot of kids that [start] hustling, they just wanna buy the latest pair of Dunks, latest pair of Jordans, and their mom might not be able to pull the sneakers. You gotta go outside and get those latest sneakers, you’re gonna hustle to get them.

“To be accepted, you have to have a certain sneaker, you have to have a certain outfit on … Like the guy with the last shooting [in Southwest], he was getting teased by people every day. And he just snapped … Just because he didn’t fit into this narrative of ‘What’re you supposed to be?’ You don't fit what we doing, you’re corny, you’re an oddball, so now we’re going to tease you … And now you can put it on YouTube or social media so everybody can see.

“I think social media and materialism, for my culture, harms us so bad … You only wear a jacket for one season. Our shoes, one scuff, they done, throw ‘em out. How crazy is that, though? … On social media … they see things that’s not in their grasp … That costs money. How you gonna get some money? The street – maybe part of a gang, maybe of part of a clique … And now they’re part of something, now they’re accepted.

“No one is telling them a different way … It's hard to change a thing, because that's all they see, that’s all they hear, that’s all that’s on the TV screen … They want financial stability, which doesn't have to be millions, but they’re seeing Puff Daddy, Beyonce, and all these people … It takes time for a person to realize they don’t need a million dollars to live … But that’s all they see, so they’re just chasing something they’ll never obtain.

“I feel PUA [pandemic unemployment assistance] hurt us in a way, because you’re giving a young man 10, 20 grand that might have nothing, then he got 20 grand. They were buying a lot of clothes. They’re buying the best liquor, they’re buying the best weed. Once the money was gone, how can that young man still afford the image he had with the money? … He created an image he can't afford to keep, so what is he gonna do to keep that image?

“I was happy when schools adopted the dress code, because with the uniform you don't have to compete with what I'm wearing. It makes it easier. Like being incarcerated, you wear the same colors. So what makes us different? Our personality, because when I got on doesn't matter. So I’ve been trying to paint that picture: Forget what she's wearing, look at her as her intelligence.

“Incarceration taught me how to be an individual because you can only spend so much … You can’t floss in jail, because you’re not able to … Everybody does the same, we all got browns … You can’t do much for looks, so everybody now gotta know you for you. On the street, you still gotta do everything for the image, [to] be seen as someone.

“The really weird thing is you’re really incarcerated with criminals, so half the conversation is usually, ‘What we gonna do when we get out?’ Still criminal activity … You wanna go in there with the positive thinking, which is not the most cool thing to do. Even incarcerated, if you want to be good, you’re looked at like you're doing some strange … I had to say I wanted to do something different, and I don't care how you judge me.”

Money and Time

“Financial stability is a focus of what we do, big time … When [young people] get some money, I think it does help a lot, but then my thing is building credit … It’s still money, but you spend some, you gotta put it back, then you have to learn the responsibility of paying it back … You pay a credit card bill the same as you pay an electric bill, your water bill, your gas bill, your rent … You use water like you buy this shirt, you gotta pay it back … Now it’ll be a bank account, driver’s license, so that’s the next step.

“Coming up, nobody talked to me about credit or getting a career kind of job. It was sports, rapper, or you’re gonna sell drugs … I hustled for money, not for the fame. It was to help. I didn't care about the big cars … Seeing the struggle, I thought I gotta make some money to help my mom … So my narrative now for young kids is it doesn't have to be sports, it doesn't have to be music, but get something that is a career that can hold you down and secure you … Try to go to school, get a diploma … trade school, the service, but something outside of just going on the corner and just doing nothing.

“Money is key. But the next step is going to be time. Your money’s good, but now what’s up with your time? … Your time is more important than anything … Without time, what do we have? Nothing.

“The change was going to prison, leaving my mom. I could never see myself leaving her now, and my kids. The change was, after you’re incarcerated, you get educated that it’s bigger than money … I was incarcerated at 24, came out at 29 … Five years, that was it. That was enough. But I know guys that never come home. It’ll change everything if you really wanna be free … Now, it’s the time I spend with people that’s more valuable than any money I could spend.

“What do we do while we’re here? What's going make our name and be significant when we pass? You want it to come to your last day and … they’re gonna speak highly of you because of the time you put in with the people … When I’m gone, talk about me being a good guy … I don't care nothing about what car I drove … I wanna be missing for the time and the impact I put on people.”

Who Do I Respect?

“In my era, my neighbor could chastise me … and my mom wouldn’t get mad, she’d understand, because it's the whole block [together]. Now, you can't say nothing to another person’s child, so who do they respect? They don’t respect you. They don’t care about nobody, because can’t nobody say, ‘Hey, what are you doing?!’

“In my era you could. I had to respect everybody. I gotta say ma’am or miss so-and so. Now, they don't care … Not even in school … So it just be like, ‘Well, who do I respect? You can’t call my parents, I don’t respect nobody now.’ I think that hurts us a lot as a community.

“My mother always told me … she’s gotta know what I was doing, so you can’t surprise her saying, ‘He did that, he didn’t do that’ … I don’t think parents know what their kids are really into. You don't know what these kids are doing now, you don’t have a clue. They’re just outside.

“Accountability … If you do something, you should be accountable. Like with [ratting], If you didn’t do that, he wouldn’t have the opportunity to tell on you. That makes a person think before they do it. You can't blame him for putting you in jail if you shot the guy. If you didn’t shoot the guy, you wouldn’t be going to prison.

“We need to implement more town hall meetings, where people will come out and talk. They would get to learn … get the parents to come out and meet your neighbors. Because you live on a block and won't even know your neighbor. [We should] have block events, as we had in the past, to meet people … make it close knit.”

Credible Messengers

“As an outreach worker … you’re seeing everybody. You could walk past and hear some gunshots. You walk past and see somebody selling some drugs. And how do you approach that? You have to know the streets … I was born in North Philly, 4th and Dauphin, then moved to Southwest, so … I still touch both sides … It makes it easier because a kid will background check you. ‘Oh that’s your cousin, that’s your aunt, okay you’re cool’ … If my name wasn't good, they won’t wanna deal with me.

“I have four [participants] in Southwest Philly, 11 North Philly … Some I met driving the van, some come from court, some I already know and I bring into the program … It could just be someone on the street, walking down, giving them a brochure … Some of them are hard to get … They gotta be comfortable with giving you a phone number, letting you know where they live at. So you always got to get that trust first.

“When they see our crew, they see … we’re not the book smart people, we’re the people who’ve really been involved … The comfortability makes them engage … and we’re gonna talk about something positive or something good … I'm trying to get more involved in other community events going on in other areas, trying to set up a food drive, be part of a bookbag giveaway for the kids, a clothes drive … The more they see we do, the more they realize that it’s really something really good going on. They’re seeing people that was on that side doing this now.

“You realize a lot of them really want help, but they're scared to say, because your neighbor might look at you funny because you really want help. That blows my mind. Like, ‘Can you give me a flyer?’ ‘Why’re you whispering?” Because of a neighbor. Might be they don’t want him to identify [with us.] So it’s like, my god, we are so lost. It can be somebody 50 years old that still will be talking crazy.

“You can’t save everybody. You put forth the effort to try, but some just don’t want it. But then when someone’s friend gets hurt, sorry to say, they call back … So you gotta try to stay in contact with everybody.

“We have a shift, but this job is really 24 hours, because any given time you get a call, I don’t have to go on the clock to help somebody out … I went to one of my participants’ graduation. I wasn't on the clock, but that didn’t matter. I’m off Monday, but if you call me Monday, I’m gonna come by and see you.

“As long as we’re here, we’ll be with them in the program … I might move a person from high-risk to medium-risk … if I think their mentality changed … You’re still with us, but I’m not calling you as much anymore, because I gotta focus on these other guys. But now, I got you to help me. Maybe a guy started out four years ago, now he’s got a job. Shows it’s possible. He was crazy too, he was bad … If they know him, that’s even better, because they know how he was five years ago. Look at him now!

“So I want [to work with participants] forever, if I can … It always helps you to have credible people … So I try to keep everybody I have. They still call my phone, I still call their phone … It’s like a family bond, I feel it never stops.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Interview and portraits by Tia Yang | July 2023