Nadine Holliman

North and Southwest Philadelphia

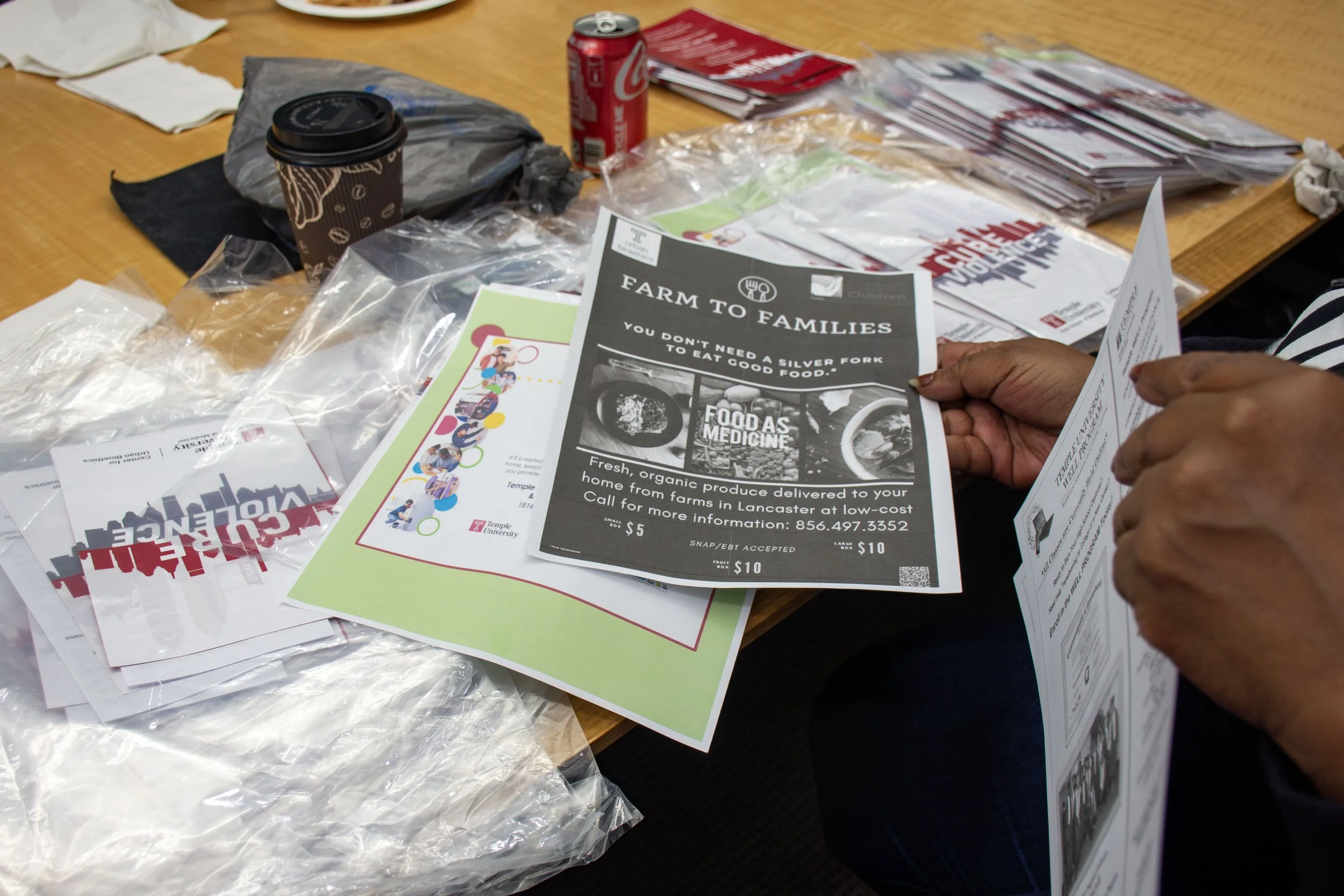

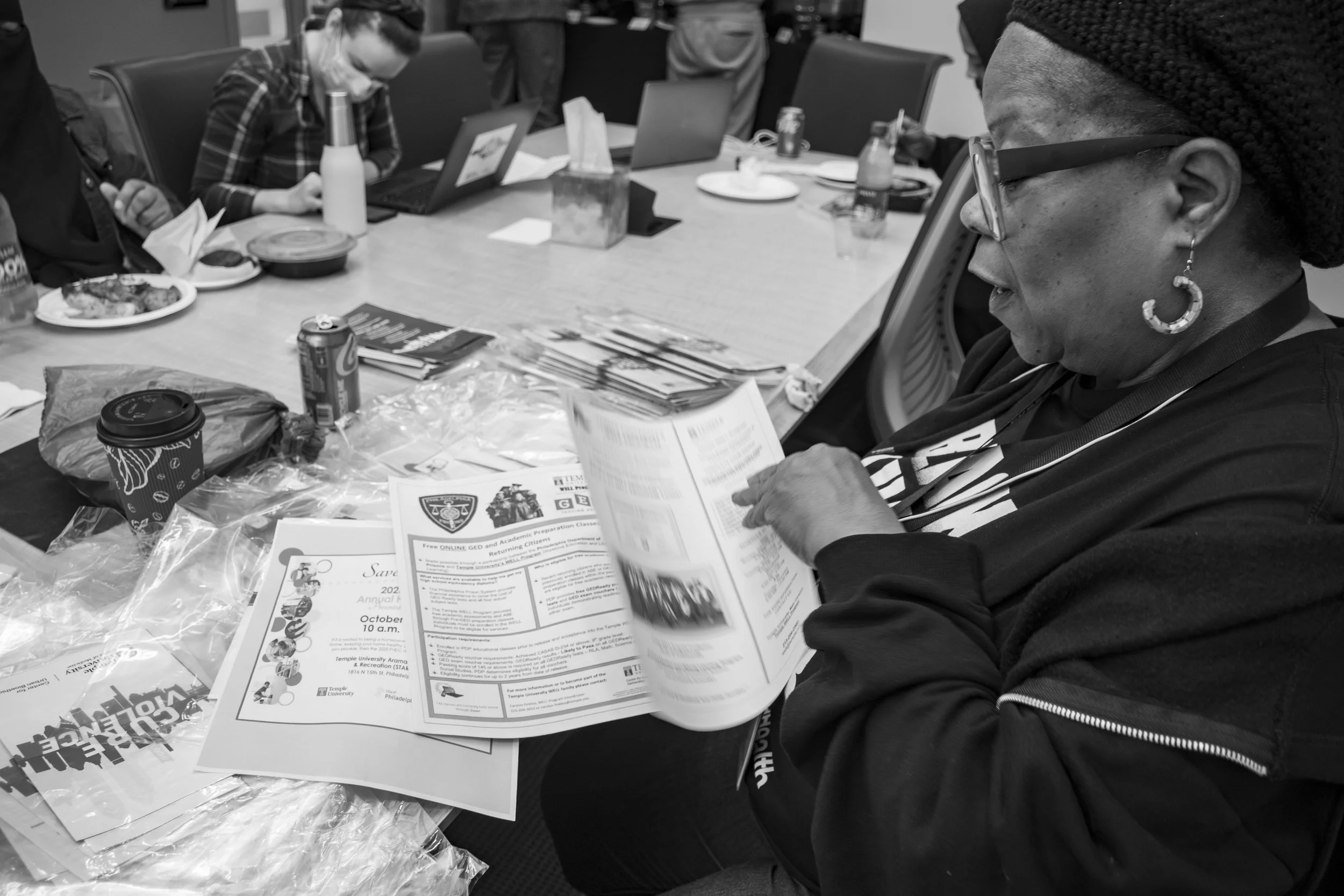

Nadine Holliman is rarely without a flier or a door hanger bag full of information on community programs and resources. She spends her days sharing these resources, or in court advocating for victims of violence and co-victims of homicide. Holliman has always been passionate about helping others in her community navigate the systems that are often so difficult to access for Philly’s Black and low-income residents — something she became well versed in as a foster child growing up in Southwest Philly and later a foster parent, raising her daughter, niece and nephew in North Philly.

Holliman had been working part-time for the Nicetown CDC and the school district in 2008 when a friend told her about a victim services advocate job with the Anti-Violence Partnership of Philadelphia. “It can't be no different than what I already do, on a personal level, in my community,” she thought.

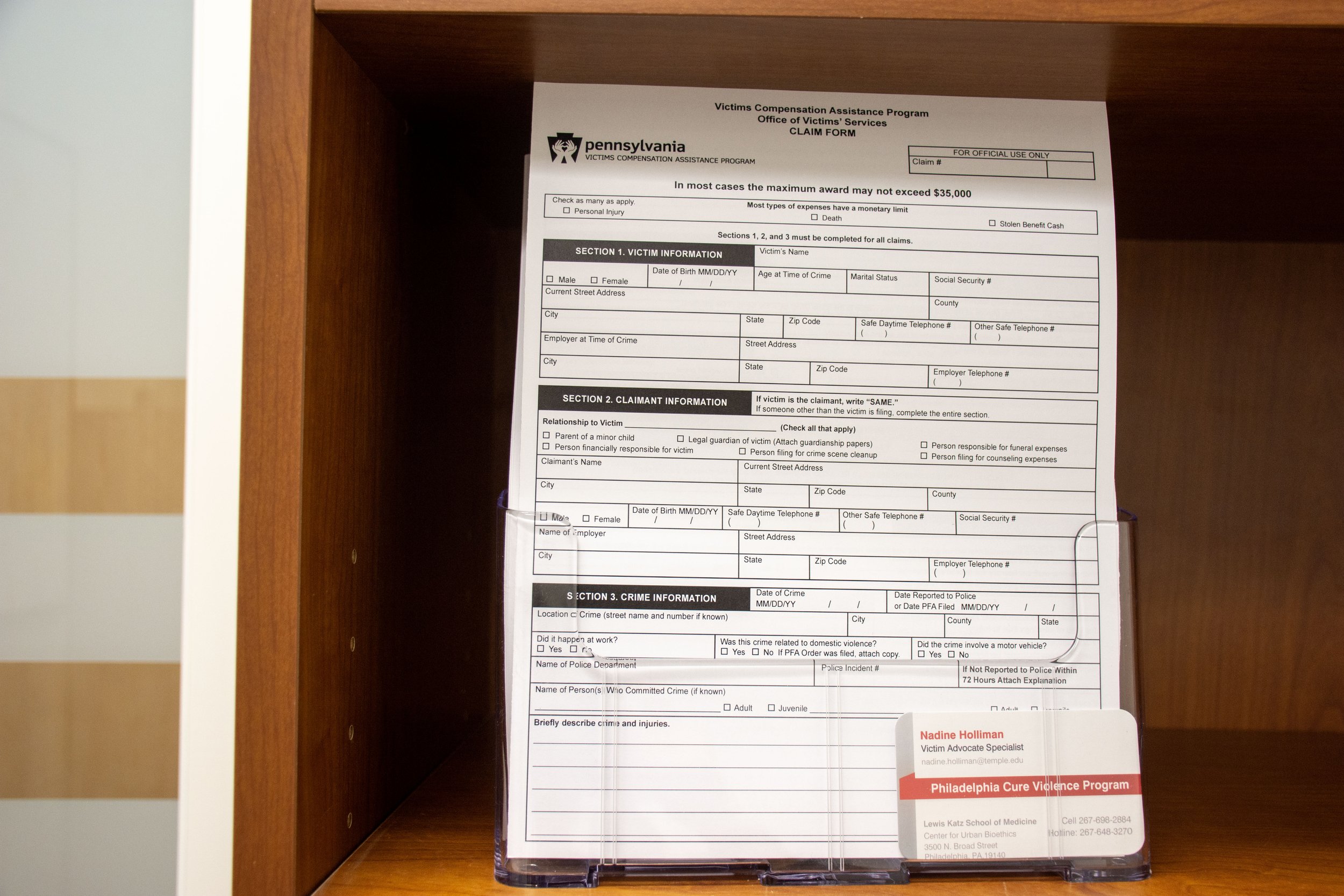

She worked in that role at AVP for 8 years before moving to Cure Violence Philadelphia, where she still works as a victim advocate specialist. Holliman helps victims of violence and co-victims of homicide navigate the legal aftermath of tragedy, supporting them in court and helping them file victim compensation claims. Equally important, she helps them navigate the human side, referring them to counseling or lending an empathetic ear as they go through an often drawn-out and retraumatizing legal process.

She’s also expanded her role to include the title of resource specialist. In this capacity, Holliman embodies a holistic approach to addressing violence as a public health issue, helping program participants navigate rental assistance applications, health insurance, summer camp options for their kids, and much more.

In the Know

“People talk to me, I talk to people. I've always been interested in being in the know, knowing what's available in our community, being able to tell folks about it. I'm all about resources … Because in my community, Black and brown communities, we don't know a lot about resources, what we can utilize in our communities, because nobody's given us that information. So that's why I do the door hanger bags … And if they didn't utilize those resources, then the next conversation they have, they will pass that information on.

“It’s just something I do, I’ve always done … because I had foster children. I have one daughter, and I raised my niece and nephew. I had to find out what was available to myself and my family, especially my nephew, who had disabilities. Because he needed services. He needed resources.

“I was in foster care at the age of eight to 15. The foster family that I went into, they just wanted me, but I had two other siblings in foster care. I spent Christmas with them, and it was just so nice. But I told them I wasn't gonna leave my siblings. I’m the oldest. I said, ‘Find us a home where we all can go’ … So they took on my brother and sister too. It was a loving home … I had good foster parents, had a relationship with my birth mother, a relationship with my father sometimes, but the thing is, I saw both worlds, so I could choose the good and the bad, and the in between. So I was given a choice. A lot of these young folks aren’t given a choice.

“I'm really passionate about young folks. I'm passionate about the older folks, because I think we should reach everybody … You just can't focus on that little kid. You gotta focus on adults too, communities and families. Let's say our victim doesn’t need victim resources, but they might have health issues, food issues, finance issues … They might say, “You know what, my son and my daughter need summer camps. You know any summer camps? I can't pay a lot.” I’ll say, “Have you got an email address? I’ll send you a list.” Now their kids are off the street because they have resources for different camps, in the county and outside of it … They can see a different environment. You know, a lot of our kids haven't been mountain climbing or hiking or ziplining … Some kids on my block, they haven't been to an amusement park. Their whole summer’s on the block running up and down the street. So what do I do? I go get my door hanger bag. I don't want to hear them kids all summer long. They need to be doing different stuff.

“And it’s important to have programs that really can help. You need the right kind of resources … These programs and these organizations have to get up, get it together …That's why we did a resource fair this summer. If it's a job fair, I want to know when these vendors and training programs come that our clients are actually going to get certified, get a job … Like the Philadelphia Youth Network, they got our students working papers right there on the spot … And programs for re-entering citizens, because these people matter. It does not matter that maybe at one time this person had a record. This person can change their life around … But we have to make things happen.”

The Victim Came from Somewhere

“The thing is with victims of gun shootings and families who lose loved ones to gun violence, if the person is caught, it takes a long time for them to go to trial. Sometimes years … The victims are being retraumatized with every hearing.

“You never imagine that your child or your loved one can walk out the house and get gunned down by some stupid person. You never think that. So when you go to court, you think the justice system is going to do right by you and your family. And then when you get in court to the prelims, [there’s a continuance] because there's not enough evidence, or maybe the offender's attorney didn't show up, maybe the Assistant District Attorney didn't show up.

“And then when the evidence comes up, let's say, you have a family, they have a video, and they see their child, or their husband, or their wife getting gunned down. And the offender, you can clearly see them, and they're saying that's not them. Yes, that's retraumatizing.

“I’ll go to court with crime victims, co-victims of homicide … When you go to homicide court and the victim’s family is on one side, the defendant’s family on another side, it’s intimidation that goes on. When I spot it, I’ll say, ‘Look judge, this is going on in the courtroom.’ That shows my clients that I'll fight for them … Some of the ADAs think that there's no human factor. So I’m like the buffer between the victim or the co-victim and the DA's office.

“I think some ADAs should be more transparent to co-victims. Even if they don’t come to court that day, they need to call the families and let them know what happened … I have a client who the ADA is not even contacting at all. She's calling the office a number of times, but I believe that they're looking at this person as a pest … But this is the family’s loved one. Now don't get me wrong, you have some who are very empathetic and very supportive of the families, but some are not, because they're thinking about their caseload.

“They're not thinking about that family, that mother, that father, who lost their loved one, and keeps coming back to court to a continuance … I think the ADAs should have sensitivity training. I think they should talk more with the families, cause the victim came from somewhere, someone.”

Grieving

“I have a client who I'm attending court with Thursday, lost her only child to gun violence. And in the beginning, oh man, I didn't open my mouth to say anything. Because she was grieving. A he was shouting. She was angry. And as time went on, I noticed her calming down a little bit. Each day was getting a little easier. She's not completely there. And she said she needs closure … The earliest the trial could be is [in a few months], but some people wait longer, four years … I admire her so much because although she was grieving the loss of her son, she’s fought for him.

“Dealing with folks who lost loved ones to gun violence, it’s hard. You have to be empathetic. I myself lost folks to gun violence, so I know … Outside people say, ‘Oh, you should be over that.’ I have a client who I still speak to and she lost her son over five years ago. And she has her good days and her bad days. Birthdays are bad, holidays are bad. But she tells me that people will tell her, ‘You should be over it.’ … People can be insensitive because they don't understand. Especially if you lose a child or a husband to gun violence. That's hard. I can only imagine if I lost one of my kids to gun violence. That scares me. And for these families to go through that, and folks to be insensitive to them, it makes me angry.

“I always tell my clients everybody grieves differently. Everyone reacts differently to a loss. So however you're grieving, you do it on your own time … They want to know, how do I get past it? But we don't know how you can get past it. All we know is day by day. Day by day.

“I have referred many of our clients to counseling … But a lot of times there's a huge waiting list. I would like for us to have our own counselor. So I oftentimes will keep in contact with victims, co-victims of homicide, and we'll just have conversations. They know they can call me. And some of them don't want counseling, they just want to be able to express themselves, have someone listen to them … I've talked to my clients for an hour, two hours at a time, because that's what they need.”

A Gun in My House

“I'm not gonna talk about deaths. But how gun violence has affected me personally is that it makes me more aware of what's going on, what's needed. I know in my community, I've seen a lot of my young men killed, and it's heart-wrenching because without resources, without programs, it’s going to continue. Because our young folks, our men, do not have a place to go. In my neighborhood, I see guys on the corners, you know doing their thing. I can't put them down, because they're trying to survive. I don't know what kind of home they come from, but they're trying to survive.

“I remember when my nephew was about 16, I was working at the curfew center on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, and he was out on the street being reckless. He decided he wanted to be a drug dealer. He decided he wanted to walk around with guns. I remember my three-year-old grandson found a gun in our house. And he comes up the steps: “Go go go go, pow pow pow pow.” So I come out of my room and he’s got a gun in his hand! I mean, a gun! Who in the hell has a gun in my house? So, that scared me to death. I told my daughter about it, and when she got home from work, she just went ballistic. My nephew came in the house, and he said, ‘Auntie, can you give me that gun?’ I said, ‘Hell no’ … I got rid of it.

“My nephew, for Mother's Day, he bought me chocolate-covered strawberries. He knows I love them. And he wasn't working. I asked him, ‘How did you get the money?’ I said, ‘If this is drug money. I don’t want it.’ So I threw the strawberries on the ground and walked away … But a lot of parents don't do that. They just let their kids be. They allow them to destroy their lives, as long as they’re bringing in some kind of money.

“When he finally did get arrested, I was waiting to go to work. We was all sitting out on the porch. He was down the street, and all of a sudden I see these cops, and I see him, and he’s got his hands behind his back. He's 16, but he's with older adults … The cop explained to me what's going on. A neighbor says, ‘He's just a kid, he don't know what he was doing.’ I said, ‘Mind your business, this is not yours. Officer, do what you got to do.’ Took him to the station. They arrested him and everything, because he had drugs on him.

“He had a court hearing, he had to do this program, he was on probation. In six months he was going straight, going to school … Well to this day, he has a record, but he knows that I don't play that shit … To this day, he always says, ‘Thank you, Auntie.’

“Why I do the things I do, why I don't tolerate a lot of stuff, I believe stems from how I was brought up. My children say that I have no tact, I just say whatever. But I don't. I think I say what's needed.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Interview and portraits by Tia Yang | October 2023